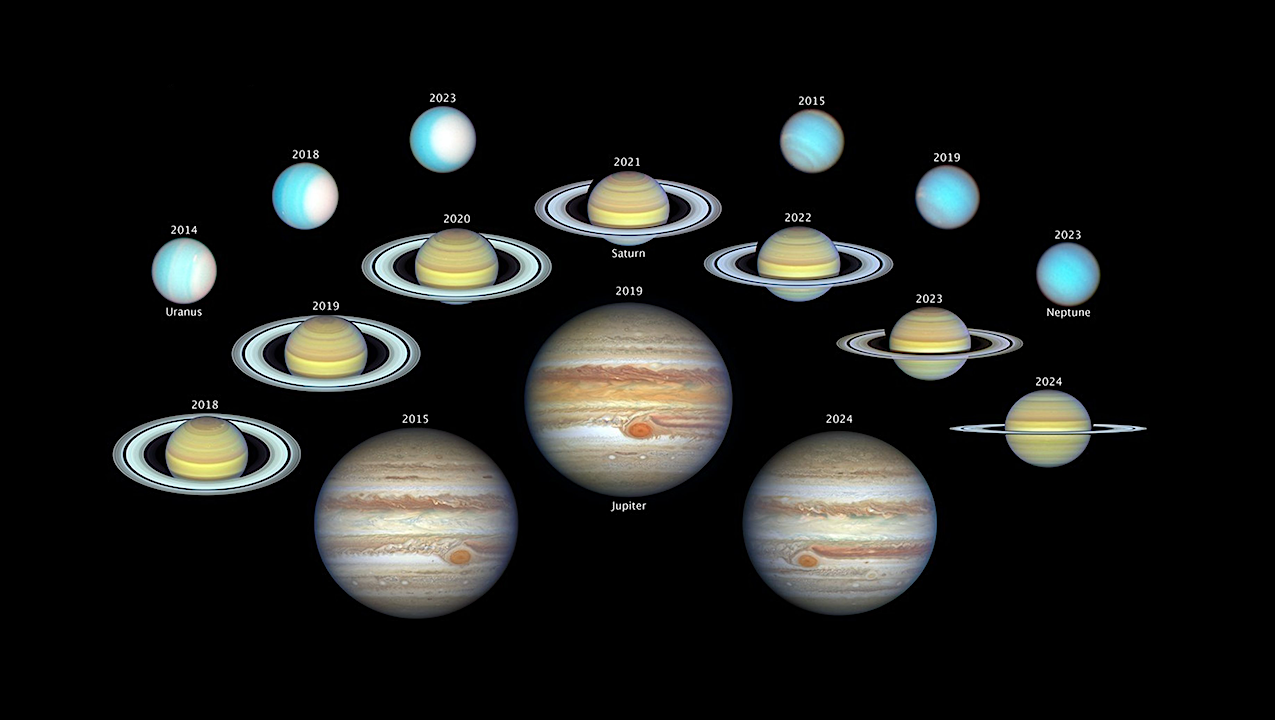

This is a montage of NASA Hubble Space Telescope views of our solar system’s four giant outer planets: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, each shown in enhanced color. The images were taken over nearly 10 years, from 2014 to 2024. This long baseline allows astronomers to track seasonal changes in each planet’s turbulent atmosphere, with the sharpness of the NASA planetary flyby probes of the 1980s. These images were taken under a program called OPAL (Outer Planet Atmospheres Legacy). NASA, ESA, Amy Simon (NASA-GSFC), Michael H. Wong (UC Berkeley); Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

Encountering Neptune in 1989, NASA’s Voyager mission completed humankind’s first close-up exploration of the four giant outer planets of our solar system. Collectively, since their launch in 1977, the twin Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft discovered that Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune were far more complex than scientists had imagined. There was a lot more to be learned.

A NASA Hubble Space Telescope observation program called OPAL (Outer Planet Atmospheres Legacy) obtains long-term baseline observations of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune in order to understand their atmospheric dynamics and evolution.

“The Voyagers don’t tell you the full story,” said Amy Simon of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who conducted giant planet observations with OPAL.

Hubble’s image sharpness is comparable to the Voyager views as they approached the outer planets, and Hubble spans wavelengths from ultraviolet to near-infrared light. Hubble is the only telescope that can provide high spatial resolution and image stability for global studies of cloud coloration, activity, and atmospheric motion on a consistent time basis to help constrain the underlying mechanics of weather and climate systems.

All four of the outer planets have deep atmospheres and no solid surfaces. Their churning atmospheres have their own unique weather systems, some with colorful bands of multicolored clouds, and with mysterious, large storms that pop up or linger for many years. Each outer planet also has seasons lasting many years. (The James Webb Space Telescope’s infrared capabilities will be used to probe deep into atmospheres of the outer planets to complement the OPAL observations.)

Following the complex behavior is akin to understanding Earth’s dynamic weather as followed over many years, as well as the Sun’s influence on the solar system’s weather. The four distant worlds also serve as proxies for understanding the weather and climate on similar planets orbiting other stars.

Planetary scientists realized that any one year of data from Hubble, while interesting in its own right, doesn’t tell the full story of the outer planets. Hubble’s OPAL program has routinely observed the planets once a year when they are closest to the Earth.

“Because OPAL now spans 10 years and counting, our database of planetary observations is ever growing. That longevity allows for serendipitous discoveries, but also for tracking long-term atmospheric changes as the planets orbit the Sun. The scientific value of these data is underscored by the more than 60 publications to date that include OPAL data,” said Simon.

This payoff continues to be a huge archive of data that has led to a string of remarkable discoveries to share with planetary astronomers around the world. “OPAL also interfaces with other ground- and space-based planetary programs. Many papers from other observatories and space missions pull in Hubble data from OPAL for context,” said Simon.

The team’s decade of discovery under Hubble’s OPAL program is being presented at the December meeting of the American Geophysical Union in Washington, D.C.

[Many more images](https://science.nasa.gov/missions/hubble/nasas-hubble-celebrates-decade-of-tracking-outer-planets/) at NASA

Astrobiology