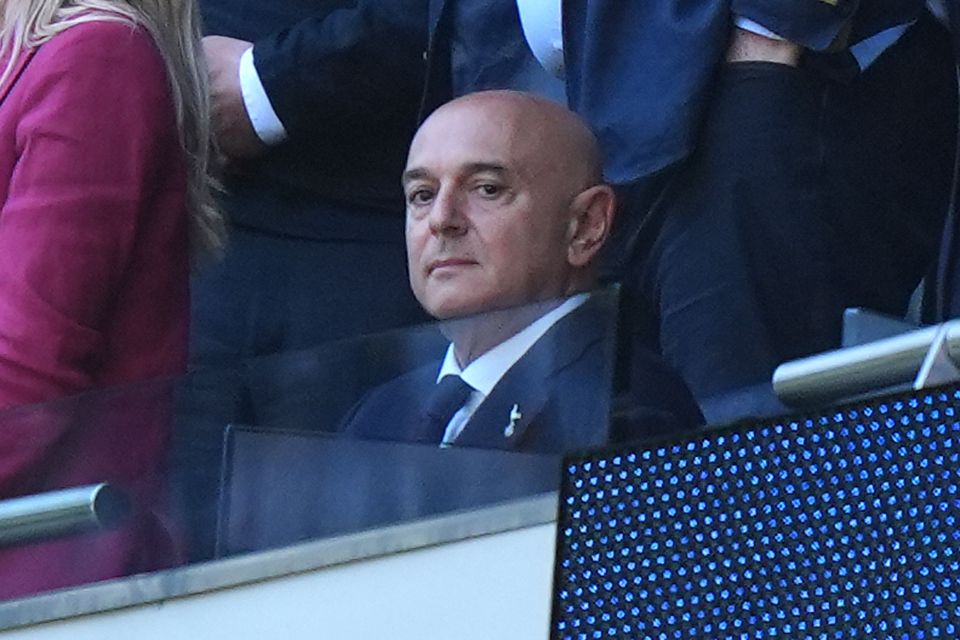

Daniel Levy (Bradley Collyer/PA)

A new ownership group could take over Tottenham and speculation is mounting that Daniel Levy is open to selling the club.

Should Levy sell, he will bring a remarkable 24-year period to an end. Under Levy’s ownership, Tottenham have qualified for the Champions League seven times, including reaching the final in 2019, and finished in the top six of the Premier League in 13 of the last 16 seasons.

While Spurs finished an abject 17th in their most recent Premier League campaign, the Europa League triumph ensured a return to the Champions League.

Along the way, Spurs have consistently outperformed sides who spent far more. An analysis of Premier League spending from 2010-20, by Stefan Szymanski, the co-author of Soccernomics, showed that Tottenham paid £2.02m per point earned in the Premier League.

The next best-performing member of the so-called “Big Six” was Arsenal, who spent £3.44m per point − almost twice as much as their north-London rivals.

Now, after years of playing the transfer market with aplomb, Levy faces an even more challenging question: how to put a price on his club?

Those involved in evaluating teams speak of a “capital premium”. For prospective investors, Tottenham’s greatest asset is the club’s location.

London is uniquely appealing to potential owners, because of the ease of travelling to the capital and the city’s wider attractions. For a billionaire who wants to entertain and negotiate business deals at their football club, London teams have the greatest cachet. No club exploit the geographical advantages that London provides as well as Spurs.

Tottenham Hotspur Stadium opened in 2019. The original projected cost was £305m; instead, the eventual costs were £1.2bn. But while the costs soared, the ground is the realisation of Levy’s vision of building a club who can exploit their geographical position.

Most simply, Tottenham Hotspur Stadium is very big: the capacity of 62,850 is the third-largest in England, below only Wembley and Old Trafford. In 2023-24, the club earned a total of £105.8 million in match-day revenue, across all competitions − the third-most in the Premier League, below only Manchester United and Arsenal.

Yet the stadium’s biggest asset is that it is more than just a football ground. The ground’s retractable pitch is ideally suited to hosting lucrative non-football events. The stadium has a licence to host up to 30 events outside football each year.

For artists, the stadium is widely considered the second-most attractive in London, below only Wembley. Beyoncé is currently midway through a six-date tour at the venue.

This year, Spurs are hosting 15 concerts, comfortably the most of any Premier League club.

Arsenal, by comparison, are hosting just two; their stadium is also 13 years older than Tottenham’s. The contrast illustrates why, although Arsenal have been far stronger on the pitch in recent years, industry insiders believe that the difference in the financial worth of the clubs is relatively small.

As well as staging concerts, Tottenham’s stadium was also designed with hosting other sports in mind. The ground has a guaranteed agreement to host a minimum of two NFL games a year until 2030. Should the NFL one day include a franchise based permanently in London, Tottenham Hotspur Stadium would be the prime candidate for a home ground.

More than any other Premier League club, Tottenham have developed a multi-purpose stadium. The upshot is that the club do not need to play football at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium to make money, though they are opaque about how much they generate from non-football events.

Such multi-purpose use is particularly desirable in the era of stringent Premier League profitability and sustainability rules. As Newcastle United have found, even billionaire owners are limited in what they can spend if their clubs do not generate enough revenue.

Spurs’ more lucrative operations outside the game allow the club to spend more than rivals who earn the same from football matters.

As PSR has become more onerous, the Premier League’s broadcasting rights are stagnating. The new £6.7bn contract, which runs from 2025-29, is less impressive than it sounds. Per season, the value is just four per cent more than from 2016-19 − a real-terms cut of around 30pc − even as the number of games broadcast has swelled to 267.

“We certainly have peaked as far as broadcasting rights are concerned,” says Kieran Maguire, the author of The Price of Football and a lecturer at the University of Liverpool. “The battles that we used to see between BT Sport and Sky Sports which kept the rights going up no longer exist.”

The growth of piracy, through means such as illegal Fire Sticks, has also undermined broadcasting rights.

Overall, Premier League clubs generate around 60pc a year in broadcasting rights, Maguire calculates. But this figure is likely to decline in the coming years, leaving clubs more dependent on other sources of revenue.

On one level, the change in the broadcasting market is bad for Tottenham: all Premier League clubs will suffer from the new landscape. But the shift is also good for Spurs’ relative attractiveness compared to other clubs, with teams becoming more reliant on commercial and match-day revenue.

“Spurs are very well equipped to deal with PSR,” Maguire observes. The club consistently have among the lowest wage-to-revenue ratios in the league.

Last year, Spurs’ wage-to-revenue ratio was 42pc, the best in the Premier League; the overall average was 66 per cent.

Tottenham had the fifth-largest revenue in the Premier League in 2023-24, £528m. The easiest way for Spurs to maintain, or improve, this position is to generate further cash from their stadium.

Especially with the allure of Champions League football, Nic Hamer from the consultancy Oakwell Sports Advisory believes that the club could generate approaching £2m a year for a naming-rights deal. For a 15-year deal, that would equate to up to £375m. With this source of revenue so far untapped, prospective buyers could potentially name the stadium after their own company or business, rendering Spurs particularly attractive.

Tottenham already have a staple of strong commercial partners, including AIA and Nike. But “there is still room for growth” commercially, Hamer says.

Vinai Venkatesham, Spurs’ new chief executive − who did the same job for Arsenal from 2020-24 − will now be charged with increasing the club’s revenue further. One promising project is the 180-room hotel and apartments on the stadium campus, which should be completed by 2028.

Two central factors undermine Tottenham’s potential attractiveness to investors.

The first is debt. Spurs have about £900m of debt, which would come off the valuation of the club. Yet around 90pc of this debt is paid at a fixed interest rate of three per cent per year, according to Oakwell Sports Advisory. The bulk of the club’s debt paid for the stadium, which is delivering the revenue growth envisaged.

Debt levels ballooned during the pandemic, which disproportionately affected clubs that generate a greater share of revenue from match days: Spurs lost about £200m in revenue from 2019-21. From registering a profit in five straight financial years until 2019, Tottenham recorded a loss of £330m in the next five financial years.

More than debt, a greater concern is dwindling performance. Last season’s 17th-placed finish continued a trend of recent underwhelming Premier League campaigns. From finishing in the top four every year from 2015-19, Tottenham have only come in the top four once in the past six seasons.

Indeed, the club have actually spent more than in previous years, but fared worse on the pitch, partly because of the loss of Harry Kane.

But the squad have still adhered to the focus on developing young players: Lucas Bergvall and Archie Gray are two teenagers already thriving in the first team. Even underperformers will retain significant resell value.

The biggest question of all is the Champions League. Even with England currently having five Champions League places each year, the competition to reach the tournament is brutal. Together with the old Big Six, Newcastle will also expect to make the Champions League each year. Aston Villa and Brighton and Hove Albion are among the other clubs who harbour realistic hopes of qualification, too.

With the Champions League, Tottenham can expect to earn revenue in the region of £600m next year. But investors will have to assess whether they can expect such returns every year. The club earned £528m in 2023-24, when they did not feature in European football’s elite competition.

Any potential investors will also have to assess the terms of sale. Enic Group currently owns 86pc of Tottenham’s shares. This is split between Levy and his family, who own 29.9pc, and the family trust of the British businessman Joe Lewis, who owns 70.1pc of Enic’s share capital.

An option to buy a majority stake is particularly attractive, as it would give investors more control over the future direction of the club. But whether Enic would be prepared to sanction a full sale, or only a share of its stake, is unclear.

Football clubs are like fine art, says the sports economist Szymanski. That is, the value is not dictated purely by market forces, but also by ego and vanity. For a billionaire, a football club is an accessory, made even more desirable because elite clubs are rarely for sale.

Still, industry insiders say that there is a general trend in the valuation of clubs. In general, a club’s expected valuation is in the region of five to six times the annual revenue.

Tottenham’s annual revenue for 2025-26 has just received a hike, thanks to Champions League qualification. This means that the club should earn about £600 million next year, giving the club an enterprise value of £3bn-£3.6bn. The club’s debt of £900m must then be deducted from this figure, giving a total value of £2.1bn-£2.7bn.

Within that range of £600 million, there are a series of questions. Tottenham’s excellent credentials to thrive in the PSR era drive up the potential price.

To put that figure in context, last year Jim Ratcliffe bought a 27.7pc stake in Manchester United for £1.25bn − giving the club an overall value of £4.5bn. This suggests Tottenham now are worth around three-quarters as much as United.

Chelsea, who were sold in 2022, attracted £2.5bn. The comparatively low figure was partly due to the circumstances of Roman Abramovich’s sale, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But it also reflected the age of Stamford Bridge, and how the ground is far less adept at generating revenue, from football and non-football activities alike, than Tottenham Hotspur Stadium.

The upshot for Spurs is that £2.5bn − separate to paying off the club’s £900m in debt − represents the minimum likely to be enough to secure control of the club.

This would give Tottenham an implied value of £3.4bn. Levy would surely be loath to accept any less.