[](https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/western-huayna-potosi-glacier-bolivia-1140x640.png)

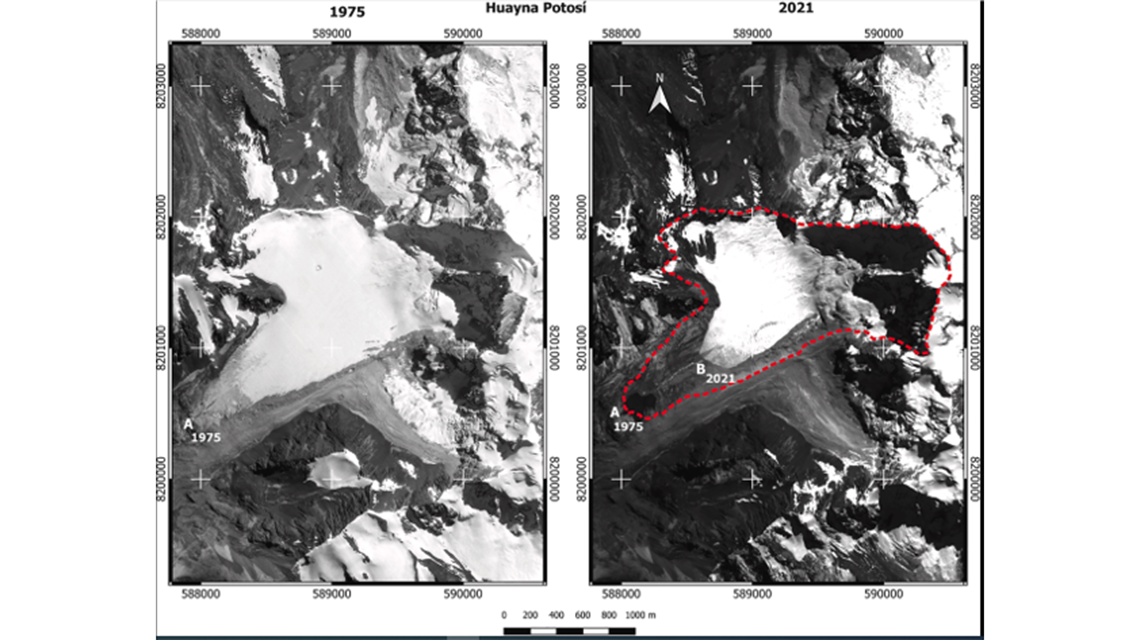

If current trends continue, the Western Huayna Potosí’s glacier—important for drinking water—could vanish entirely in twenty years. (Photo: Edson Ramírez)

The device will stay long after the scientists descend, transmitting signals beyond the mountains via satellite—a digital memory preserving information about what the ice can no longer hold.

“Current glacial retreat now functions as a thermometer of accelerating climate shifts, with its rapid pace signalling the urgency of rising global temperatures,” says Gerd Dercon, Head of the Soil and Water Management and Crop Nutrition Laboratory of the Joint FAO/IAEA Centre. “As the ice melts and refreezes, it reveals not only the changes in climate but also the fragile dependencies human civilization has on these frozen reservoirs.”

In the valleys below, hundreds of thousands of people depend on the glacier’s water. Llamas and alpacas graze in the fertile grasslands, their pastures fed by the seasonal meltwater that has shaped this high-altitude ecosystem for centuries. Farmers equally rely on it to irrigate their crops and feed their livestock, while one million inhabitants of El Alto, a city close to Bolivia’s capital La Paz, depend on it for drinking water.

For generations, these ice fields have served as an unspoken contract between the mountain and those who live in its shadow, releasing water at a pace that allowed life to flourish. Now, that contract is breaking.

The reasons are clear. Rising global temperatures are melting glaciers around the world, but here in Bolivia, the crisis is accelerating. Sediments from ice-free areas are transported by strong winds and deposited onto the glacier, darkening its surface and increasing heat absorption.

By analysing sediments released from areas now exposed by glacial melt and accumulating in lakes and reservoirs, scientists are not only tracking the effect of the retreat of the ice on sediment distribution but also uncovering broader environmental shifts. These climate-driven changes may impact soil fertility, water quality, and water chemistry.

Cyclical weather patterns like El Niño amplify the warming, causing erratic swings in precipitation and rapid melting. Scientists predict that if these trends continue, the Western Huayna Potosí’s glacier—important for drinking water and once thought eternal by the locals—could vanish entirely in twenty years.

“Stopping the retreat of the glacier will not be possible,” says Dercon. “But we have to capture the water in several ways.” In Bolivia, communities have built more reservoirs, including smaller ones, dredged some old ones and raised the walls of dams. The land also needs to be worked differently, shaped to hold water rather than shed it, the soil taught to embrace. In this, reforesting the area with native trees and halting overgrazing of hungry llamas and livestock are fundamental changes for supporting healthy soils and land regeneration.