The story of the 1995-96 Premier League season belongs unquestionably to Kevin Keegan, albeit not for the reason he would have liked. The Newcastle campaign has become English football’s locus classicus of the Nearly Men, or the One That Got Away. Whenever the story is told, other than by the red half of Manchester, it is usually in tones of sighing, head-shaking regret. In horse racing terms, the team did a Devon Loch, the queen mother’s horse that collapsed 40 yards from the winning post at the 1956 Grand National. Yet Devon Loch’s name is now enshrined in sporting legend, and who remembers the name of the winning horse that day?

Keegan’s personal popularity was undiminished that year. When Labour held its party conference at Brighton in October 1995, Tony Blair almost fell over himself to get an audience with Keegan, who had come to town for a fringe meeting. There is famous footage of the two, both in white shirts, playing head tennis with a football. “At last,” said Blair, “I have done something to impress my children.” Aged 42, Blair was then the coming man, preparing the ground for the general election two years ahead. Maybe he thought he could learn something from Keegan’s gathering momentum as the people’s favourite. In any case, in the autumn of 1995, Keegan’s Newcastle side were being hailed as “the entertainers” and “the neutrals’ favourite”. The team were carrying all before them, and with a swagger that almost defied belief: this was the club that had fought off relegation from the Second Division only three years before.

Manchester United fans questioning Keegan’s mental stability in May 1996, when British beef exports were banned due to BSE

At the beginning of the new year, Newcastle were 12 points ahead of their nearest challenger at the top of the table, Alex Ferguson’s Manchester United. Their form began to falter. I can still recall the hope and dread I felt for Keegan and his team, leaping from one game to the next like scaffolders on heights. It looked vertiginous up there.

The ominous buildup of stress came to a head one evening at Leeds United’s Elland Road. A few weeks earlier, Man Utd had narrowly beaten struggling Leeds. Ferguson, with sly insinuation, said he hoped that Leeds – United’s fierce cross-Pennine rivals – would put in the same effort when Newcastle played them. In the event, Newcastle beat Leeds 1-0, but the memorable part of the occasion came afterwards in the tunnel at Elland Road.

Interviewed from the Sky studio by Richard Keys and Andy Gray, Keegan looked underslept and his brow was thunderous. He also sported a pair of outsize headphones, which may have deceived him as to his volume level.

Keegan: “I think things have to be said ... I think you’ve got to send Alex Ferguson a tape of this game, haven’t you? Isn’t that what he asked for?”

Gray: “Well, I’m sure if he was watching it tonight, Kevin, he could have no argument about the way Leeds went about their job and really tested your team.”

Keegan: “... I mean, that sort of stuff, we ... It’s been ... We’re bet – we’re bigger than that.”

Keys: “But that’s part and parcel of the psychological battle of the game, Kevin, isn’t it?”

Keegan: “No! When you do that with footballers, like he said about Leeds … I’ve kept really quiet. But I’ll tell you something: he went down in my estimation when he said that. We have not resorted to that. But I’ll tell you – you can tell him now, he’ll be watching it – we’re still fighting for this title, and he’s got to go to Middlesbrough and get something, and ... and I’ll tell you honestly, I will _love it_ if we beat them – LOVE IT!”

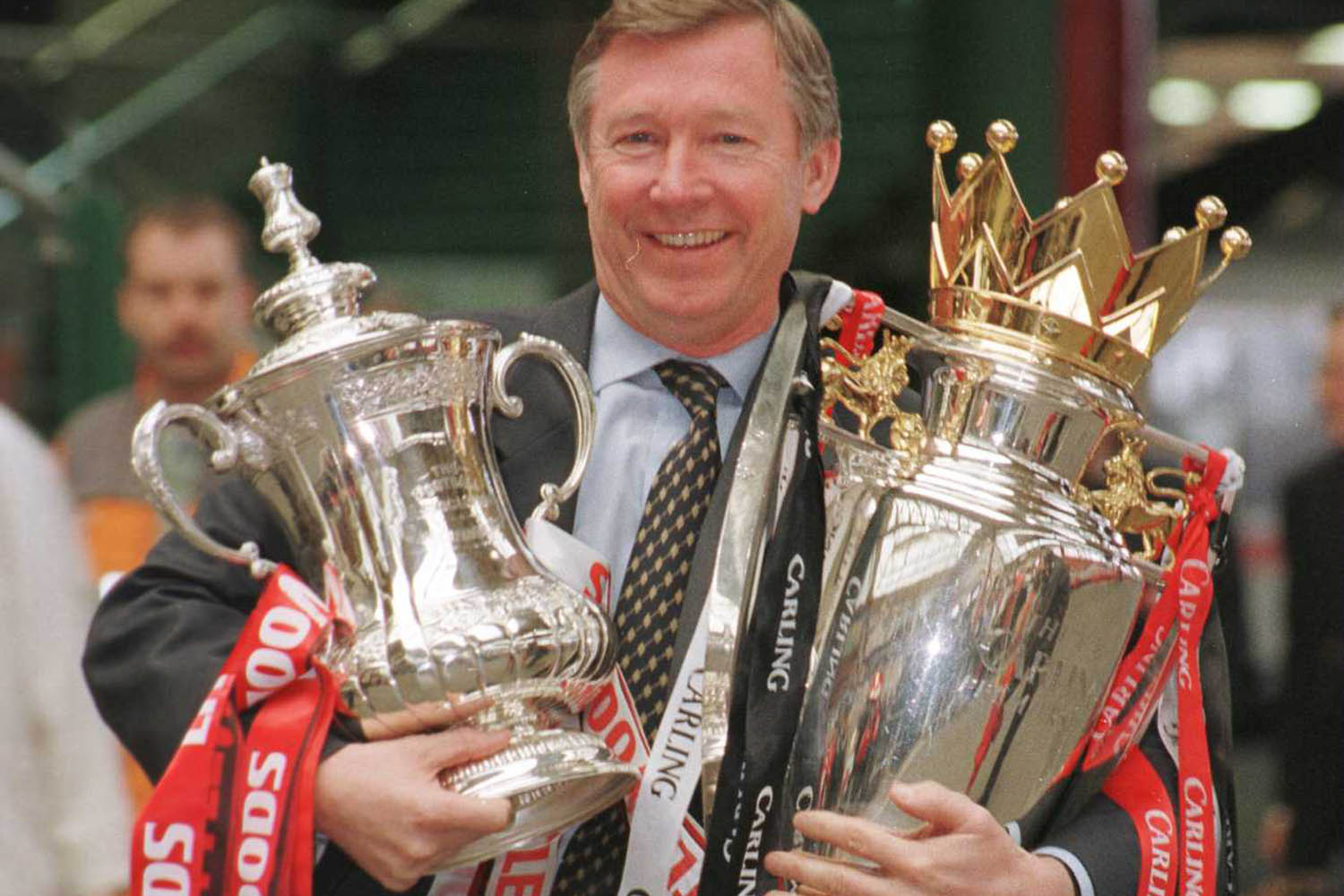

Alex Ferguson with the FA Cup and Premier League trophy in 1996

The jabbing of his finger, the hoarseness of his voice – you could almost hear Ferguson tittering over in Manchester. The Keegan rant has become football’s equivalent of Peter Finch throwing a wobbly in _Network_ (“I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take this any more!”). It’s his proclamation of integrity, and something more. When Keys refers to the “psychological battle” intrinsic to the game, the vehemence of Keegan’s reaction is revealing. He appears to regard Ferguson’s attempt to psych him out as not only unfair but outrageous, insupportable – dishonest. But, of course, it worked.

In his essayistic memoir _The North Will Rise Again_ (2023), Alex Niven candidly admits he has never quite recovered from Keegan’s “heroic failure” of 1996. “In common with many people from the north-east, I seem to have internalised the fairytale of Keegan’s Newcastle over the years, so that few things I have experienced in the intervening years have come close to emulating this utopic digression of the mid-90s. This is the full, real, absurd and tragic implication of what it means to believe in the possibility of a messiah.”

Niven identifies this belief as both comforting and stupefying, since it keeps alive the flame of romantic myth and at the same time reconciles the believer to accepting things cannot change without a semi-divine intervention. Will ye no’ come back again? He calls this messianic fervour a “vast melancholic illusion”, particularly strong among the northern English. Bereft of faith in political leaders, or in the dinosaurs of the monarchy and the church, many in the north find their meaning in football – the club, the esprit de corps, the manager.

I condole with Niven and understand his messiah theory. But I would not count that season a failure. It’s only a failure if you regard winning as the be-all and end-all. The memories are enough; they are much more than enough. I wonder if Keegan has come round to that way of thinking.

_Photographs by Allsport, Getty Images_